In my search for my grandmother’s PRAJS ancestry 15 years ago, I wound up purchasing a scan of every single vital registration from every archive in Poland with the surname PRAJS that I found in an index. If I was lucky, there was an LDS film (the images photographed by the Mormon Church in the 1970’s from all the archive documents) or there was a microfiche copy in the Beit Hatfutsot Library or in the CJS (Center for Jewish History Library in NYC). But when I exhausted those resources I had to bank wire funds to the Polish State Archive Branch where the specific books were housed. [Today of course, , JRI-Poland has most of these scans and should be the first-stop resource for anyone doing Polish genealogy research.]

Recently I worked with a researcher who wrote to me that the surname PRASA was in her ancestry, and we discovered that her family was from Dzialoszyce and Pinczow, two of the towns for which I am the JRI-Poland Town Leader and had extracted the records that are in Polish.

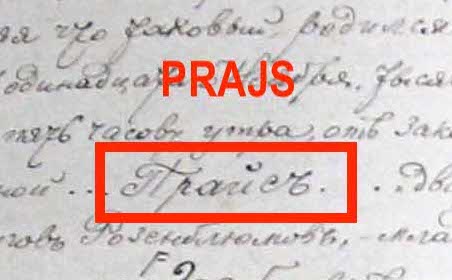

There were three birth registrations in Pinczow that I examined in Cyrillic, and discovered that in all, very clearly, the mother’s maiden name spelled PRAJS, not PRASA. Perhaps I found a new cousin! The researcher, however, was adamant that her ancestor’s surname PRASA, and here’s what I found: In the Dzialoszyce records, the same mother was indeed shown with the maiden name PRASA. So why did the Pinczow clerk write “PRAJS?”

The PRASA were an indigenous Dzialoszyce Clan and appear in the Dzialoszyce Book of Permanent Residents. There were PRAJS in Dzialoszyce as well, but they were permanent residents of Wislica. In Pinczow, the surname PRAJS was common, but there isn’t a single family with the surname PRASA appearing in 100 years of records from that town. There are many PRAJS (who settled early in Pinczow but migrated from Wislica). So the Pinczow clerk was very familiar only the surname “PRAJS” and that’s what he heard when these birth testimonies were given and that’s what he wrote.